HISTORY

THE RUSH TO BONANZA

The Klondike gold rush is known as one of the last great gold rushes. It left a lasting cultural legacy, and many books and poems, as well as a few movies, were made to commemorate it. Even now, the great gold discovery is celebrated every year in Yukon on Discovery Day.

What made it such a big deal? Aside from the huge amount of gold that was found, it all had to do with the timing. When the big gold strike was made at Bonanza Creek in 1896, the United States was going through a bad economic depression. People were having trouble finding work and making enough money to feed themselves and their families. Because of this, the chance to become rich by finding gold in Yukon appealed to a lot of people.

This was also around the time that the American frontier (also known as the Old West or the Wild West) began to disappear. From the time that the United States was first colonized by Europeans in the 1600s up until 1890, there had been a steady wave of Americans spreading out across the country. During this time, they built houses and started farms on land that had previously been occupied by Indigenous peoples. Much of that land was undeveloped, and had yet to be drastically altered by humans living there.

Now there were so many people living in America that there wasn’t much undeveloped land left. It seemed that the country had already reached its limits. But for people who longed for the “good old days” of the Wild West, where they could live in an area that had yet to be developed, and work hard off the land to earn their fortune, the Klondike seemed like one last chance to do just that.

Founding of Dawson City

By the end of August in 1896, pretty much all of the miners in the Yukon region had made their way to Bonanza and the entire creek had been staked. Many miners were already finding good amounts of gold in their mining claims.

There wasn’t as much gold in the Klondike region as there had been in California, but it was concentrated in a much smaller area. Miners who were lucky enough to stake a claim at Bonanza Creek made a fortune. Most of the claims in that creek each had about half a million dollars worth of gold in them. In total, almost $30 million of gold was found at Bonanza. That’s over $1 billion in today’s dollars!

On August 31, 1896, several men decided to search a small creek that flowed into Bonanza. To their excitement, they found gold there too! They named this creek Eldorado.

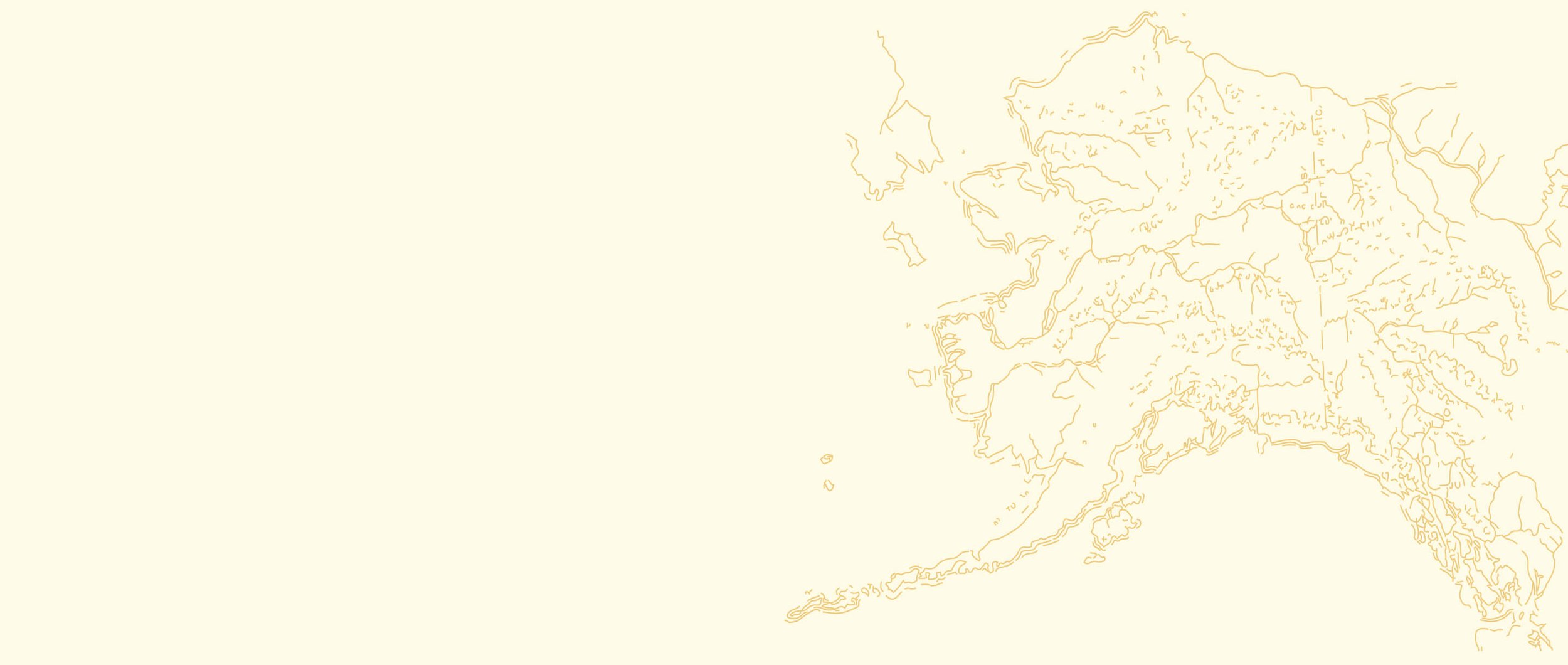

Map of the Klondike Gold Fields. Note Bonanza Creek and Eldorado Creek, where large amounts of gold were found.

Source: Adney, T. Klondike and Indian River Gold Fields. 1898. Barry Lawrence Ruderman Map Collection. Stanford University Libraries.

“An economic depression is a serious financial crisis that might last for many years. People can lose their jobs, go bankrupt, and even have trouble buying food and other important items. The Great Depression of the 1930s is the most famous economic depression, but other serious ones have happened throughout history, such as the one that took place from 1893-1897 in the U.S. This depression didn’t last as long as the Great Depression, but for a while it was much worse.”

“A frontier is a border or an edge. In this case, it refers to the edge of developed land, beyond which is wilderness.”

“Bonanza Creek and Eldorado Creek are both tributaries of the Klondike River. A tributary is a river or stream that flows into a larger river. The Klondike Gold Rush gets its name from the Klondike River, since gold was found in several of the river’s tributaries.”

Throughout that fall and winter, miners kept searching for gold in the Klondike tributaries. Then in January of 1897, an American prospector and businessman named Joe Ladue bought a large area of government land and turned it into the town of Dawson City. He named the town after George M. Dawson, the Canadian geologist who had explored and mapped the Yukon region ten years earlier. Located where the Klondike and Yukon rivers meet, Dawson and the surrounding area had been used for hunting and gathering by the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in people and their Hän-speaking ancestors for centuries.

Panoramic view of Dawson City, Yukon, photographed from the east side of the Yukon River. The Klondike River can be seen in the background.

Source: Dawson City, Yukon. Circa 1899. William Hepworth Collection. Yukon Archives.

How the News Got Out

In the first few months after the discovery at Bonanza Creek, word spread to Alaska, and miners quickly made their way across the border to Yukon. By the spring of 1897, there were around 1,500 people living in Dawson City. A number of these people weren’t even miners; they were shopkeepers, bar and hotel owners, or people who opened up other stores in town.

Then, once the ice melted on the Yukon River that summer, the miners who had already found gold in the Klondike hopped on two small ships to exchange their gold for money down south. (There were no banks in Yukon yet.) It was these two ships that brought news of the big discovery to the rest of the world.

When people walked off the ship dragging suitcases literally filled with gold, they caused a sensation. Soon the news was everywhere, in newspapers all over North America and even Europe. There was gold up in the Klondike! Thousands of people, mostly Americans, dropped everything and rushed to make their way North. It was a stampede to Yukon and the Klondike gold fields!

For the most part, these stampeders weren’t miners. They were salesmen, streetcar drivers, bankers, and lawyers. Even the mayor of Seattle and a former governor of Washington set off for Yukon. None of these people had any experience with mining, and most of them didn’t even know where Yukon was. But they left anyway, eager to strike it rich in the creeks and rivers of the Klondike.

Routes to the Klondike Gold Fields

There were many different routes people used to get to Yukon. The easiest way was to take a ship up the Yukon River. This was known as the “rich man’s route” because it was the most expensive option. Nevertheless, ships headed for Yukon were packed full of people. They were so crowded that not everyone could fit on them, and people would have to wait for another ship to depart. The shortest and most commonly used route was through the Chilkoot Pass, but it was a difficult trip. It was called the “poor man’s route.”

A ship called Excelsior leaving San Francisco for the Klondike in the summer of 1897. This was the first ship to carry passengers up to Yukon after news of the big gold discovery got out. The ship held 350 people.

Source: Partridge, S.C. Steamer EXCELSIOR leaving San Francisco for the Klondike, July 28, 1897. 1897. Transportation Collection. University of Washington Libraries.

Some Canadians refused to take either of these routes because they passed through the United States. People tried coming up with crazy “all-Canadian routes” through British Columbia and Alberta, but none of these were very successful. Few of the people who took them actually made it to Dawson.

Unlike the Indigenous people, who knew how to travel light and had been following trails across Yukon for centuries, many of these gold seekers were inexperienced. They didn’t know what to bring, so they ended up carrying all sorts of useless junk that weighed them down.

Map of different routes to the Klondike Gold Fields. (Note: the “All Water Route” was also known as the “rich man’s route,” and the “Skagway/Dyea Route” was often called the “poor man’s route” or the “Chilkoot Pass route.”)

Source: Map of routes to Klondike. 2011. National Park Service.

The Chilkoot Pass Route

Stampeders who took the Chilkoot Pass route had to go through two Alaskan towns along the way: Skagway and Dyea. These towns were just like the ones in old western (“cowboy”) movies. There was a lot of drinking and gambling, and people were constantly getting into fights or being robbed.

Looking south along Broadway Street in Skagway, Alaska. The railroad tracks were laid in the summer of 1898.

Source: Hegg, E.A. Broadway, Skagway. Circa 1900. Anton Vogee Collection. Yukon Archives.

Panoramic view of Dyea, Alaska, along the Dyea River.

Source: Vogee, A. Dyea Alaska. 1899. Anton Vogee Collection. Yukon Archives.

The towns did have sheriffs, but were actually ruled by a crook named “Soapy” Smith and his gang of thugs. Gold seekers who were passing through were easy targets for the gang members, and were lucky to make it out of the towns without being attacked or having their money stolen.

Jefferson Randolph Smith II aka. Soapy Smith. He was killed in a gun fight on July 8, 1898.

Source: Peiser, T. Jefferson “Soapy” Smith at bar in saloon in Skagway, Alaska, July 1898. 1898. Library of Congress.

If gold seekers did make it through Skagway and Dyea, the hardest part of the route was yet to come. To get back into Canada, travellers first had to climb Chilkoot Pass. But the North-West Mounted Police who guarded the Canadian border at the top of the pass wouldn’t let anyone through unless they had enough money or supplies to last for six months. In order to get all their supplies across the border, some gold seekers had to make the trip up to the top nearly 20 times, which could take weeks! (Unless the traveller had enough money to hire packers, many of whom were Indigenous, to carry the supplies up the summit.)

A group of people, including First Nations packers, resting with their gear at the top of Chilkoot Pass.

Source: Yukoners on the Summit of Chilkoot Pass, Alaska. Circa 1897-1898. Yukon Archives.

It was a difficult climb, especially for travellers weighted down by heavy packs of items, along with their thick wool coats. By the time they got to the top, many of them were gasping for breath. Some had to climb the last few feet on their hands and knees. Then they would leave their items and slide back down the hill to do the climb all over again.

People climbing to the top of Chilkoot Pass during the winter of 1897-98. This scene is one of the most famous in Canadian history, even though it took place on the American side of the mountain.

Source: Hegg, E.A. Packers ascending summit of Chilkoot Pass. Circa 1898-1899. Library and Archives Canada. C-005142.

There were a few women who made the treacherous climb up Chilkoot Pass. They were miner’s wives, prostitutes, or women just looking for an adventure. Martha Black was one of those adventurers. She walked the Chilkoot route in July of 1898, and made the climb to the top of the pass, all while pregnant! Martha was tough. She had left her husband before leaving for Yukon, and raised her baby alone in Dawson City. She established a sawmill at Dawson, and eventually married a lawyer, George Black, who she met there. When she was almost 70 years old, she became the second woman in history to be elected to the Canadian Parliament.

Martha and George Black along a trail in Yukon. They are dressed in fur coats.

Source: G.B. and M.M.B. 1925. Overland Trail Collection. Yukon Archives.

The final step of the Chilkoot Pass journey was to ride along the Yukon River into Dawson City. But most of the stampeders had reached the top of Chilkoot Pass in the dead of winter, and found the Yukon River completely frozen. They would have to wait several months for it to thaw. Gold seekers passed the harsh winter sleeping in tents along the shore of nearby Lake Bennett and building boats that they would use to sail down the river in the spring. Hundreds of boats had to be built, and most of the trees in nearby forests were cut down to use for lumber.

“Tent city” of stampeders on the shores of Lake Bennett in the spring of 1898.

Source: Goetzman, H.J. En Route to the Klondike Gold Fields - Scene at Bennett City - Spring of 1898. 1898. Butler Family Collection. Yukon Archives.

Once the ice on the Yukon River had melted and people could finally put their boats in the water, they set off for Dawson. It wasn’t exactly an easy ride down the river. Travellers had to steer their boats through rapids in Miles Canyon, and then the Whitehorse Rapids right after that. Many boats were wrecked along the way, until the Mounted Police stepped in and started inspecting the safety of boats before they entered the canyon.

A group of stampeders in their homemade boats on the shores of Lake Bennett in British Columbia. They are getting ready to set off for the Klondike.

Source: Leaving Bennett for the Klondike. 1898. Anchorage Museum of History and Art Collection. Yukon Archives.

After making it past the canyon and the rapids, it was finally smooth sailing the rest of the way to Dawson City. Unfortunately, by the time most of the stampeders made it to Dawson in the spring of 1898, two years had passed since the great gold discovery at Bonanza Creek. The entire creek had already been staked and most of the people who had travelled for almost a year to make it to the gold fields hardly found enough gold to make the journey worthwhile.

These three photographs show the route from Lake Bennett, B.C., to Dawson City, Yukon, along the Yukon River. The top image shows Bennett from above. The caption says: "The world's largest tent city. More than thirty thousand men built their own boats here on Lake Bennett in the spring of 1898. Each man brought his own tent and building equipment and the air was [filled with the sound of] tapping of thousands of hammers."

The middle image shows stampeder boats on a lake. The caption says: "A homemade armada sets sail. Here is a sight never before seen - and never to be seen again: seven thousand boats, loaded with thirty thousand pounds of food drifting down the green corridor of an alpine lake on a bright June day in '98."

The bottom image shows the crowded riverfront at Dawson City. The caption says: "At the end of the rainbow. This is the scene that met the newcomers' eyes: two miles of boats, six deep, jammed along Dawson City's teeming waterfront."

Source: Klondike water route from Lake Bennett to Dawson City. 1898. Bill Roozeboom Collection. Yukon Archives.

“Remember the “grubstake” system that was mentioned earlier? It’s a system that involved a trader giving supplies to a miner without being paid, with the understanding that the miner would pay them back with any gold they found. Joe Ladue had actually grubstaked Robert Henderson, the man who said he should be credited with the discovery that set off the gold rush, a few years before gold was found at Bonanza.”

“Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in means “people of the Klondike River.””